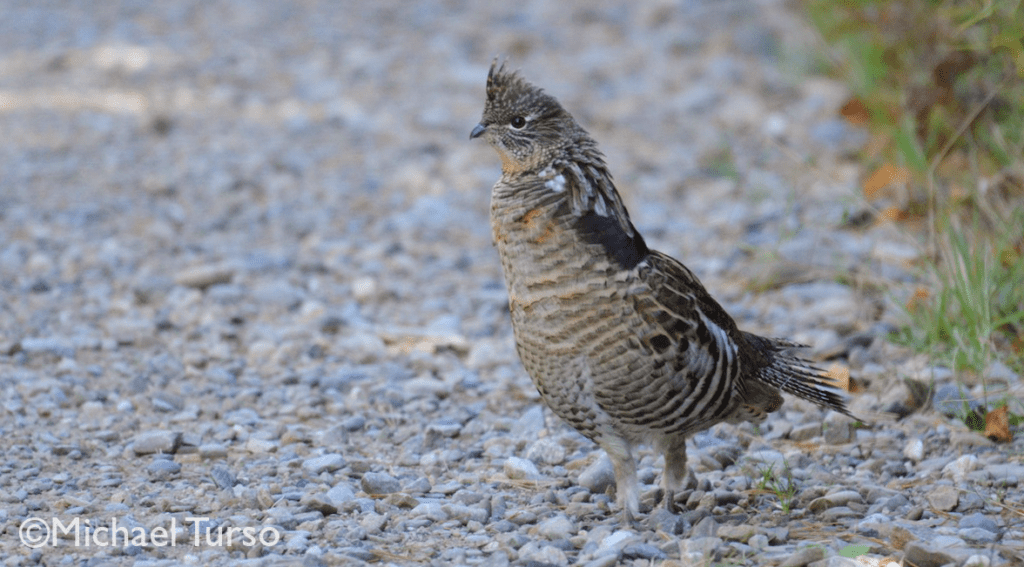

Better known as Partridge, or “pahtridge” depending on who you are talking to, the Ruffed Grouse is a common game bird in Maine, the closet thing we have to a native chicken. Most encounters with Ruffed Grouse are a brief, quick views of their rear end as they blast off into the woods. As a prized take for a hunter (described as a “mild, tangier chicken”), these grouse are generally quick to leave the scene before ending up on a dinner plate. However, several times each year I get reports of “tame” Ruffed Grouse that are very approachable, photogenic, and even chase after people. So what is up with these birds?

I’ve heard two explanations for this:

The first, which I think is more common, is that the bird is territorial. Ruffed Grouse are not often physically aggressive (most birds aren’t because of the risk of self injury) but are typically very territorial, especially during the nesting season. We often hear of grouse that are following people around, sometime even riding on snowmobiles, tractors, or trucks. The amount of energy spent on this behavior seems like only something a nesting/territorial bird would do. Simply put, a Ruffed Grouse’s one goal is to make copies of themselves so they will invest as much energy as it takes to find a mate and defend their territory.

The second explanation, is that this behavior is a “throwback” to how grouse previously acted, before they were hunted. There is a great quote in Forbush’s 1927 Birds of Massachusetts about this: “When the country was first settled, this bird was one of the most tame and unsuspicious of the fowls of the air. It was known as the “fool hen.” It was so tame that many were killed with stones or knocked over with sticks. They were even fair game for the small boy. Forty-five years ago in the wilderness I saw birds of this species that walked boldly up to within a few feet of the hunter, or even sat on a limb just over his head. An occasional unsophisticated bird may be seen now even in souther New England that will seek human companionships, and even allow itself to be picked up and handled, but such birds are rare and usually are short-lived. Where they are hunted, the survivors have become “educated,” and they resort to all kinds of tricks to escape the hunter and his dog.”

You can read that whole account here: https://

Ora Knight’s 1908 Birds of Maine has another great quote, without as much detail, but says, “They have learned by experience how to act.”

We should note there is a second species of grouse in Maine, the Spruce Grouse, which is more commonly known for their tame behavior. Knight’s account for this species reads: “They rarely fly up until practically stepped on at other times than in the nesting season., and in the nesting season a broody hen will hardly leave the nest for anything. Birds I have seen perched in trees, where they are easier to discover then when on the ground, remained until having completed my inspection I either secured them by shooting or with a club or walked away and left them there. Those seen by me at Sunkhaze, a few miles from Oldtown though in a region frequently visited by the hunters, were so take as to appear stupid.” The behavior in this species is generally attributed to the lack of hunting pressure; they is no open season for Spruce Grouse in Maine.

So there are a few possibilities for this behavior, and probably many more that we can’t yet or will never understand. Perhaps in some places with lower hunting pressure these “old” behaviors survive in a few birds. In any case, it is best to give birds plenty of space, especially if we are entering or in the breeding season. Any time you are making a bird change its behavior, you are too close. Eye contact, or a bird looking at you, is often the first sign you are too close. Also, a quick rule to remember: Grouse don’t want to be your friend, and especially not your dog’s.

-Doug