Fall is upon us and birds are migrating. While many of us think of birds leaving for the winter, this also means the potential for vagrancy and rare birds showing up almost anywhere. Hotspots, like Monhegan Island, have already seen rarities like Say’s Phoebe, Painted Bunting, and Red-headed Woodpecker in the past week.

On Saturday, September 16th, Angus King III spotted a very off-course vagrant in the North Meadow at Maine Audubon’s Gilsland Farm: a Fork-tailed Flycatcher. Word got out immediately and in the first couple days we’ve seen a few hundred birders make the trek to Gilsland and see the flycatcher!

Where to go:

Through the entirety of its stay, the bird has been seen in the North Meadow, located on your right as you pull into Gilsland Farm. There is parking all along the side of the road there but plenty of spaces further down the driveway at the Environmental Center. The bird has fallen into a pattern of spending the mornings and evenings feeding on the deep blue fruit of Arrowwood Viburnum (Viburnum dentatum) — there is a cluster of this it is favoring near the west side of the North Meadow at the base of a lone White Pine with a few apple trees growing around it. As it warms up and insects start flying around the bird relocates to the large elm along the northern edge of the North Meadow, next to the large grayish house that abuts the property.

Why is it here?

Let me start by saying this has nothing to do with Irma. Or any hurricane. Ever. Hurricanes have the potential for displacing birds but this species has a well documented pattern of what we call “reverse misorientation.” **I’ve been calling it mirror-image migration but referring to Rare Birds of North America by Howell, Lewington, and Russell I realize that reverse misorientation is a better classification and birders are just crazy enough to really care about that.**

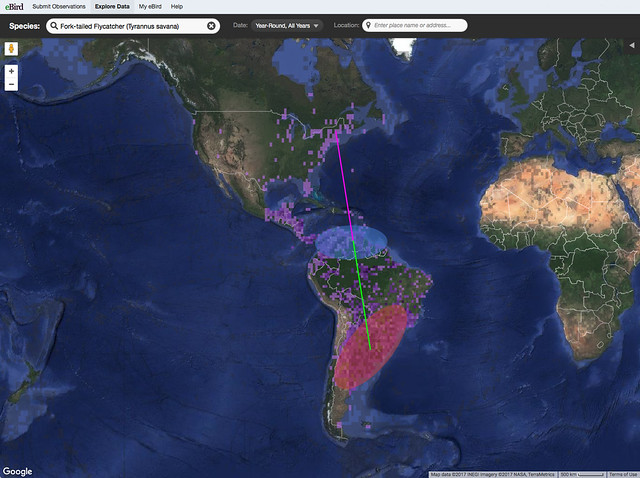

Before we dive into the map below to explain how the bird ended up here, it is worth pointing out what subspecies this bird belongs to. Fork-tailed Flycatchers has four subspecies ranging from the resident monachus in Central America, sanctaemartae and circumdatus resident in northern South America, and savana which is migratory and illustrated below. We know this bird is from the savana group because of the ‘deep emargination’ in its outer three primaries (in the above flight shot you can see the ‘notches’ in the outer-most flight feathers) a feature that the other subspecies only show in the two outer primaries.

This map shows the savana Fork-tailed Flycatcher’s range, highlighting their ‘wintering’ area in blue and their ‘breeding’ range in red. The important thing to realize is that as a southern hemisphere breeder this bird would have just undergone its ‘spring migration’ after spending its ‘winter’ (which was our summer) in northern South America. It should migrate south (following the green line) to its breeding range in central South America but because of some presumably genetic abnormality it flew north instead (following the green line). The lines I’ve drawn are the same length and shows how this bird likely thinks that it has flown to the right location.

How long will it stay?

Everyone asks: what will happen to the bird, why is it alone, when will it leave? The best answer is “we do not know.” Every vagrant is different and this Fork-tailed is already unique in how long it has lingered. The optimistic hope is that this bird, or any vagrant, would redirect and make their way back to their typical range. This bird is so far off course and likely ‘thinks’ it is going the right way. Fortunately it has found an area with abundant food, at least until it gets much colder. Because of the uncertainty of the stay of its duration, as with most vagrants, my best advice for seeing it is to come as soon as you can. Updates will be posted on the Maine-birds Listserv or on eBird’s Maine Rare Bird Alert.

-Doug