There’s never a typical day in the life for the coastal shorebird crew, but this year, it’s even more challenging than ever. It’s hard to survey beaches and build fencing while staying six feet apart, and basically impossible to do outreach–talk with beachgoers, knock on doors of neighboring residents, hand out informational brochures–while keeping a safe and respectable distance.

But if there’s one thing to learn about the members of this year’s crew, five scientists and techs who are tasked with monitoring and ensuring the safety of Piping Plovers and Least Terns on 20 Maine beaches, it’s that they are flexible. As Coastal Birds Project Director Laura Zitske says, not only are they all great with the science of these endangered shorebirds, but they are also able to problem solve, use a tool in a new way, handle a difficult situation, ease tensions, and adjust on the fly.

The crew is part of the Piping Plover and Least Tern Recovery Project, a cooperative effort, with Maine Audubon working in partnership with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands, and local municipalities to protect and conserve these rare shorebirds.

Increasing development along the shore, including construction of seawalls, jetties, piers, homes, parking lots and other structures, has reduced the available habitat for these two species by more than 75%. The presence of more people and their pets means less suitable habitat for these birds which nest right on the sand. For more than 35 years, Maine Audubon has worked with landowners and towns to raise awareness and protect birds when they are most vulnerable. And it seems to be working. In 2011, there were 33 pairs of plovers. Last year, a record 89 pairs nested and fledged young. This year, already by May 15, 93 pairs of Piping Plovers and 44 nests have been spotted.

On a recent day in mid-May, the crew has decided to split into two teams. Francesca Gundrum and Monica Johnson are at Old Orchard Beach, where they have already seen several pairs of plovers and erected management–their term for fencing, that includes posts, twine, and signage, to keep people from walking close to nests, or “scrapes.”

While Johnson, a biologist who is back for a third year on the crew, walks up the long windy beach, surveying for birds and scrapes, Gundrum does the hard part: going to the hardware store. What would normally be a five-minute stop to get some twine and stakes, in the COVID-19 era, takes almost an hour. For Gundrum, a biologist and outreach specialist charged with interacting with the public, her first year has started in a way no one could have imagined.

She joins Johnson and they decide to move some of the management, based on signs that a pair has been scraping just outside the existing twine. This involves hammering in stakes and tying twine. If you’ve ever tried to pound a stake into sand, then you know this is not as easy as it sounds. It’s windy and cold, and they’re trying to work as quickly as possible to minimize the disturbance to the birds.

They spend some time observing one particular plover who isn’t moving as much as they’d like. Is it injured? It’s the female; we watch her head to the nest, take the male’s place, sit for a minute, but then get up and move away. Monica is concerned that the bird may have injuries that prevent her from sitting on the eggs, so they will keep a close eye on this pair.

Meanwhile, at Ogunquit, a pair has already laid two eggs and the team there, director Zitske, biologist Laura Williams, back for her second season, and Olivia Davies, a first-year bio technician, have decided to build an exclosure, a fenced-in circle topped with blueberry netting.

A plover pair will typically lay four eggs. The parents’ goal is to have all the eggs hatch at the same time, and so once there are between two and four eggs, the team will consider building an exclosure to keep people from walking on and around the nest, and to keep predators like foxes away.

The team always thoroughly discusses their options when it comes to protecting each nest. If it’s too windy, exclosing is difficult and the birds are often more unsettled. If the pair is seen flying off the nest when approached, then it’s too dangerous to exclose since the adult could attempt to fly through the netting and injure itself. On busier beaches, the birds’ behavior could be more unpredictable, but if there are a lot of predators nearby, then exclosing the nest may be the best solution. Ultimately, protecting the adults is the top priority, but the crew will do everything they can to increase the chances that a nest will be successful.

Experience has taught Zitske, a wildlife ecologist who has been at Maine Audubon since 2011, to look for all kinds of signs to know when a plover pair is finished laying eggs and ready to sit and incubate, and when conditions are right for an exclosure. She’s determined that this pair is done, so the team gets all their equipment ready.

The goal is to be as fast as possible, and disturb the area as little as they can, to make sure the birds don’t get spooked and abandon the nest. On the mark, they spring into action, pounding stakes through the sides to make sure the wire goes deep enough to keep predators from digging their way to the nest. The final step is covering the whole thing with blueberry netting or monofilament mesh and securing it as tightly as possible to keep crows or other predatory birds from getting in. In a miraculously-well choreographed twelve minutes–possibly a new team record–they are done. (In the time-lapse video above, it may appear as though our biologists are working in close proximity to one another, but they are actually all carefully practicing distancing while out on the beaches!)

Then it’s on to Wells Beach, where a pair has made a nest in an unfortunate location: right on the main path from the parking lot to the beach. The beach has been closed due to pandemic restrictions, so maybe that pathway seemed safe. But the beach is scheduled to open next week, and so Zitske has been on the phone off and on all day with various people from the state, the town, and volunteers to find ways to balance the needs of the birds with the inevitable disruption from people.

A pair of birds had laid two eggs, but a huge swell had washed at least one away. Now, there’s one egg in the nest–either they recovered one, or laid a new one–and the little bird is vocal as the crew pounds in more stakes, tightens up flagging and twine, positions the signage, and attempts to make it crystal clear that this is a no-go zone. It’s difficult work; the pathway is full of scrabble and pebbles, not the smooth sand where nests are typically found.

Curious beachgoers, one neighboring landowner, and one dedicated volunteer stop by to chat and ask questions. It’s great to spread the word, but it makes it hard to keep working. It’s also very windy, and masks make communication challenging. As Zitske pounds stakes and knots twine, she talks about what it means to help these plovers, one of whom is literally piping away at her. “People really enjoy being able to watch plover chicks. It’s pretty cool to be on the beach; you can sit in your chair and see an endangered species doing its thing right in front of you. That’s pretty incredible.”

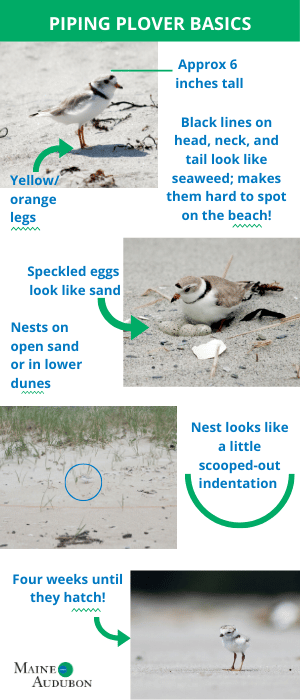

She pauses to tighten some twine. “All it takes is a little bit of awareness,” she says, “to give the birds space. They are not necessarily where you think they are. They don’t stay in the roped-off areas; those just allow room for courtship and places to nest and rest. The birds lay their nests on the open sand, and they move and use the whole beach. The chicks, once they hatch, go down to the water’s edge. They feed all over the beach. That’s something I’m always trying to get people to realize. I like to remind people that what’s good for the birds is good for the beach. Some people think it’s a hassle to have the lower dunes roped off but what’s good for the birds saves the beach.”

Though the pandemic is causing all sorts of problems for Zitske and her team, and she’s concerned about what the summer will bring, she’s finding that the birds give her much comfort. “The best thing about this job right now is just seeing the birds come do their thing, make their nests, go through the motions, and have that sense of normalcy. The rest of the world hasn’t stopped. It’s really nice to see that animals are just doing their thing.”

As the day winds down, the team communicates by phone and text and gets ready to head back to Maine Audubon’s Gilsland Farm in Falmouth, where they park their vehicles, on loan from Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Another coronavirus complication: they all have to drive in separate vehicles. This, says Gundrum, makes information-swapping harder. “The time in the car was a great time to share information and talk,” she says. “Now it all takes that much longer.” The crew used to gather at Gilsland Farm to compare notes, talk strategy, collect materials, and just check in with each other. Now, they stand six feet apart in the parking lot, next to their own vehicles, and figure out a plan for tomorrow. “And by morning,” says Gundrum, “that plan will probably need to change.” Such is the life for a flexible team protecting endangered shorebirds in Maine.

Stay tuned: We’ll have another visit with the crew once the eggs have hatched, in about a month!