On June 1, 1978, Maine’s innovative “Bottle Bill” went into effect. Forty years later, it’s hard for many Mainers to picture doing anything with their bottles and cans other than redeeming them for their deposit. But it’s worth remembering that the path to this bill was long, winding…and lined on

both sides by litter.

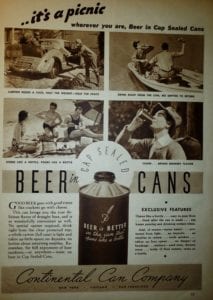

Perhaps the biggest contributing factor to states’ implementation of bottle bills was the advent of the single-use metal beverage can. Replacing reusable glass bottles, cans transformed how people consumed beer and soft drinks. They were manufactured quickly and cheaply, and sweeping marketing campaigns emphasized their convenience — in particular, how easy they were to dispose.

By the end of the 1960s, 60 percent of beers were sold in single-use cans and bottles, as were half of soft drinks (up from only five percent a decade earlier). It wasn’t long before these “disposable” containers were showing up on roadsides, riverbanks, and just about everywhere else.

That spurred Oregon, in 1971, to pass the nation’s first bottle bill, which required a refundable deposit on the purchase of beer and soft drinks. A handful of other states followed suit, including Maine, which in 1976 took up a similar measure. Following heavy lobbying by the beverage and grocery industries, an amendment was added to the bill requiring voters approve it at the ballot box in order for it to take effect.

The fall of 1976 was a battle for public opinion. “The big grocery stores went berserk,” explains former Maine Audubon executive director Dick Anderson. They launched a major media campaign urging voters to oppose the bottle bill, warning that all kinds of negative consequences would result from its passage.

On the other side of this effort was Maine Audubon. Bill Ginn, Maine Audubon’s assistant director at the time, logged over 7,000 miles driving around the state, speaking to up to five audiences a day on behalf of the measure. In the end, the referendum passed comfortably, 58 percent to

42 percent. (When the law’s opponents forced yet another referendum two years later, 84 percent of voters chose to keep it in place.)

It was a good thing, too. Research has consistently shown that bottle redemption laws are highly successful in reducing litter. A study conducted in Maine after the law went into effect found that beverage container litter dropped by 69 to 77 percent. In general, states with redemption laws have been found to experience a 75 to 80 percent return rate on redeemable containers — meaning the vast majority of beverage containers going out are making their way back after use.

So, where do we go from here? Bills in the Maine legislature as recently as this session have sought to turn back the clock on Maine’s bottle bill by reducing the deposits on some types of containers. Fortunately, with an informed and organized opposition, those bills have so far been defeated.

Rather than reducing deposits, Maine Audubon actually supports increasing them. With inflation, the value of returnables has declined substantially over the years — which means the incentive to return bottles and cans is dropping. Maine would be wise to consider an increase. Michigan, for example, has a ten cent deposit on cans, and experiences close to a 95 percent return rate.

In addition to its environmental benefits, Maine’s bottle bill supports small businesses, like redemption centers. It reduces the costs to communities of collecting and recycling these containers, and it supports local fundraising efforts through bottle drives.

Here’s to another 40 years!

Data and history from bottlebill.org and Dick Anderson. Header image by Bart Everson.

This article appears in the Summer 2018 issue of Habitat magazine. Become a member to receive your copy each season.