It’s 3 am and the cacophony surrounds me. I lie in my tent in the low angled light of a 24-hour sun, listening to the calls of Cackling Geese, Long-Tailed Ducks, Pacific Loons, Lapland Longspurs and shorebirds. Lots of shorebirds. Black-bellied Plovers, Dunlin, Semipalmated Sandpipers, and numerous others come to this unique place to breed and raise their young. The meltwater tundra ponds, abundant larval insects, and constant light create a perfect environment to raise chicks. Where is this magical place, you may ask? I am on the Canning River delta on the coastal plain of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR).

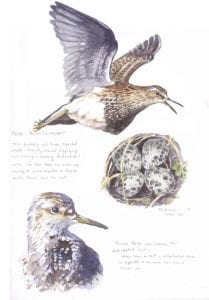

It is mid June of 2019, and I am in the remote Canning River Bird Camp as a guest of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, as this year’s Voices of the Wilderness artist in residence. They have flown me 300 miles north from Fairbanks to tell the unique stories of the birds that raise their young here, through my field sketches and eventually finished paintings. As I try to drift back to sleep in my tent, I hear one call in particular that stands out: the undulating UFO-like call of the male Pectoral Sandpiper.

It’s getting late in the season for these male shorebirds, and they need to find a mate soon. The three months of temperate weather go by fast before winter’s icy grip returns. PESA (the ornithological code for Pectoral Sandpipers) travel all the way from South America to ANWR, a journey of almost 4,000 miles.

There’s no time to rest though, as the males must fly around the tundra advertising their availability, making their unique call by pushing air through an inflated throat sac. When resting they look like little Arnold Schwarzenegger birds with their pumped-up chests, where the throat pouch lies. After they reach the Arctic plain they can cover thousands of miles circling and calling in desperation. Only about 25 percent of the males are successful, leaving plenty of lonely bachelors to fly back to South America unfulfilled.

We find many PESA nests during my stay here, so some of the males have figured it out. My timing here in the Refuge has allowed me to experience the breeding displays, finding of nests, and even hatching of eggs as the chicks begin their lives. Move over, Baby Yoda–there is nothing as cute as a young sandpiper!

Despite the constant daylight and abundance of food resources, life here rides on the edge of a knife. One bad spring storm can decimate the year’s nesting success. The other and perhaps most important feature of the coastal plain that makes it the spot for raising young is its pristine nature. ANWR is 19 million acres of habitat undisturbed by human activity. There are no roads, trails, or regular structures to interrupt the flow of tundra, river, and meltwater ponds. The birds that migrate here come from all over the globe, and connect us to what happens on the coastal plains in the Arctic. These birds, and all the other Arctic wildlife, need this pristine habitat to survive and flourish.

Speaker Series: Arctic Artist’s Journal: Michael Boardman will share an interactive presentation of stories, artwork, and lessons from one of the Earth’s most imperiled landscapes, Thursday, Feb. 13, 7 – 8:30 pm, Gilsland Farm Audubon Center, 20 Gilsland Farm Road, Falmouth. Members $12, Nonmembers $15. Register online here.